Exploring Memory, Matter, and Meaning on World Photography Day 2024

““The worst part of holding the memories is not the pain. It’s the loneliness of it. Memories need to be shared.””

In late 2011, visitors to the Foam Gallery in Amsterdam probably did not anticipate the sight that invited and then confronted them.

While it was no secret, even back then, that information overload was no longer an obscure academic term bandied about in conferences and seminar halls but a real effect driven by an explosion of digital infrastructure. It was unlikely the term realized its full impact until the moment they literally walked through Erik Kessels’ show “What’s Next” – an immersive installation of the hundreds of thousands of photos Flickr users uploaded and shared with the world in a single 24-hour period that Erik printed and heaped in the halls of the gallery.

I can only imagine, and vividly, visitors overwhelmed by the experience as they waded through memories of people heaped together, too many to see individually.

That which is largely invisible, relegated to the cloud behind individual accounts, or to folders in phones and other storage devices, was now spilling out into full view, confronting visitors with the reality of the information deluge, and their role in it.

It probably pushed them, and the rest of us reading up on it, to ponder “What’s Next” if we stayed the course – an infinite loop of click-upload-and-share. Each day producing a new set of photos even before we’ve had the time to look through and reflect upon those from the day before, each subsequent set of photos morphing over the next into an indistinguishable mass of digital matter, likely only satisfying in the realization that the moment was not ‘lost’, even if the memory of the moment was, waylaid through the viewfinder into obscurity amid the deluge of sharing.

Whatever lessons the world drew from the show likely did not last long.

There are now more places to store photos, including but not limited to social media – Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, X – and the cloud. While Erik Kessel printed 350,000 accessible photos uploaded to Flickr in a 24-hour period in 2011, I doubt if he or anyone would attempt a 24-hour period now, the numbers too scary to contemplate.

The deluge is near total, the social feeds a raging river of images rushing past, blurring content and contexts in equal measure before melding into an impression of having “seen” them but barely remembering any, emotions scarcely registering, memories even less so.

And yet we continue to photograph. Driven. Compelled. As if an invisible force animates within the desire to place a frame in space and find out what materializes within, a means to see the world around us and allow the ‘seeing’ to shape our view toward life and the world we inhabit. To affect, and be affected.

““I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed.””

It led me to the inevitable question, one that’s been posed before by many too many over many years – why do we photograph, and to what end if there indeed is one, and how does photography, to those of us involved in the craft, center us in our own lives?

I put the question, and a few more, to three photographers who’ve distinguished themselves with their photographic eye, and as curators of three ephemere. photo books — Satomi Sugiyama, Colin Czerwinski, and Marci Lindsay.

What followed, and it wouldn’t have turned out any other way, were distinct approaches with differing perspectives even while converging toward the centrality of image-making, ‘seeing’ – the viewfinder and the eye as natural extensions of one another, converging to the singular, mediators to the world within and without, a window to memory, feeling, and emotion.

Life creeps in on us when we least expect it. What starts off as a curious indulgence, stays on. Soon it becomes a habit, a routine whose demands do not weary but elevate the moment, the day, and life.

Soon purpose finds us, and the pursuit of the fleeting moment becomes an end in itself, enchanted by the possibility that the unexpected and the uncertain is attainable.

When did you first come to realize that photography would come to occupy an important place in your life?

Satomi — About 20 years ago, I was introduced to the world of Lomography and learned to experiment and simply have fun shooting film without worrying about technicality. Obviously the technical aspects followed right after, but I think what made photography so important in my life was that it gave me so much joy to create.

Colin — I'm not entirely sure, but starting NOICE back in 2015/16 and continuing with it today shows that photography holds significant importance to me. While I enjoy creating my own work, what truly motivates me is seeing how NOICE inspires others. Hearing that our content motivates and inspires people to take pictures is incredibly rewarding.

Marci — Photography entered my life as a young child, maybe 10 years old, when I discovered the work of photographers such as Brandt, Erwitt, Lange, Winogrand, and others, in a book called The Family of Man. I fell in love with street photography then, although I didn’t know it was called that. It wasn’t until my kids were grown (and I was on Instagram) that I realized that the photography I loved and had been drawn to for a half century, had a name and was being done by a community of people around the world. That’s when I started to challenge myself and to shoot in the street.

Do you see the world around you differently without a camera in your hand?

Satomi — Yes, and no. I think once you are a photographer, it would be impossible to see the world like you did before. While I might be able to enjoy the moment with the people around me more when I’m not carrying a camera, I often end up seeing something I wish I could capture on film!

Colin — No, I don't. Even without a camera, I mentally compose images. It's a constant practice and a form of meditation.

Marci — Although I got a camera as a child and started taking pictures back then, I’ve spent most of my life without a camera in my hand. Even so, I have always been a keen observer of people—I’m always watching! I studied film in college, writing my thesis on Italian neorealism, considered ‘slice of life’ cinema and which often featured non-actors. I started a career early on as a city planner in New York. Reading the classic book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs led to an interest in the question of how to maintain the culture of life in the street, which Jacobs explained was vital yet disappearing in mid-20th century US cities. So even though I’ve only picked up a camera to make street photos in the last decade, my work now reflects, to a large extent, the way I’ve seen the world my entire life.

A photograph frames facts — the reality of the space it bounds, focusing the eye to the elements and their placement while drawing the mind to the possibilities they hold. It makes me wonder what lies beyond the frame, nudging my mind to extrapolate from what is within, seeking to fill gaps between knowing and not knowing. It is on this spectrum between seeing and wondering that life takes shades that make it meaningful.

To wonder is to wander life’s tangents.

How has photography helped you see the world, and shaped your perspectives toward life?

Satomi — I think photography helped me become more imaginative and observant than I was before. I really enjoy finding stories in people’s mundane life or finding beauty in less than “perfect’ things I never paid much attention to before. I’m especially drawn to older things whether it’s buildings or clothing, for example, because they often have more histories or stories to tell. I find beauty in things that I know can be gone at any moment if I don’t document them while I can.

Colin — Photography teaches you to focus by framing your subject and omitting distractions. It’s the art of seeing, refining your vision to identify what’s interesting, beautiful, or humorous, and learning to see patterns, beauty, and significance in even the most ordinary subjects. It's about honing the ability to notice details that might be overlooked by others.

Another key aspect is paying attention to light, which is the true subject of every photograph. What we perceive as physical objects in our photos are actually just photons of light. So, in a way, "seeing" in photography is about understanding and capturing how light interacts with the world around us. It's less about whether you're "seeing correctly" and more about developing your own unique perspective on how light reveals the beauty and patterns in the world.

Marci — I think the way I see the world and my perspectives about life have shaped my photography, and not the other way around. Of course, once I started shooting, it did heighten my awareness of my surroundings even more and got me to slow down. I’ve noticed that I’ve accidentally inspired some of the non-photographers in my life to notice more of what’s going on around them, and to see more like a street photographer! I think that’s the point of what we do, no?

I'm not sure it [photography] has made me slow down in life in general! I also have been practicing yoga for 17 years, but I'm not sure that's helped either. I'm pretty much like most people, addicted to the phone, multitasking to the detriment of everything, many times, and trying to cram more things in 24 hours than is possible.

Share a photograph you’ve taken that crystallizes your idea of what you want your photography to convey to the viewer, and your thoughts around it.

Satomi — This is a really hard one because my photography is pretty different depending on whether I’m doing portraits, street photography, or my current ongoing cat and the city double exposure series. But there’s one thing I always look for no matter what kind of photography I’m working on, and that is the storytelling aspect. Whether it’s from the subjects’ emotions or relationships between the main subject and their surroundings, I like to bring out the stories that are often raw, cinematic, and ambiguous.

Colin — I don’t aim to convey a specific message. I simply photograph what I find interesting. If others also appreciate it, that’s great.

Marci — It’s challenging to pick just one photo to represent my work and my outlook, but one contender might be this one called Debajo, (San Sebastian, Spain, 2019). It is a humorous moment, but also one which in reality happened in just a few seconds, almost surely one that no one else noticed and is now preserved. It’s got just enough mystery; I’ve been asked many times what she was looking at or fetching from under the car. That remains a mystery, even to me. It also has pattern and a limited color palette. Color is important to my work, but I don’t want it to become a distraction.

In what way does a photograph speak to you? Share an image by a photographer you return to often, and the feelings it evokes in you.

Satomi — I’m very drawn to black and white surreal photography, and Shoji Ueda’s Sand Dune series has always been a huge inspiration for me to the point that I’ve even done a tribute to this particular image. I really like that his Sand Dune series has such a nostalgic feeling, but it’s also surreal at the same time.

Colin — It’s not so much photography itself that speaks to me, but the content within the photographs—the colors, the juxtapositions, the light. Photography is the medium I use to explore the world and myself. I admire William Eggleston for his way of seeing the world, which resonates with me. His images often make me laugh subtly or bring a sense of ease through their simplicity. You have to be wise enough to find gold in mud, so to speak.

Marci — Another challenge—just one photo?! Well, I return often to almost anything by Helen Levitt. She captured life in the streets of New York, but her work reflects such universal themes. This photo catches a fleeting moment, a bit of mystery, as well as humor and a huge dose of joy.

A photo book that’s left a lasting impression on you, and why?

Satomi — My boyfriend recently gave me Rambles, Dreams, and Shadows by Arthur Tress, and I am absolutely in love with the book! I’ve been a huge fan of his photography for a long time, and his dark and haunting black and white portraits have always inspired me when I’m creating my work. I think surreal photography can easily become cheap and cliché if they are executed poorly, but his visions, skills and executions are all like no other!

Colin — I have several William Eggleston books, but I recently got one by Garry Winogrand, whose work I also admire. Winogrand’s focus on people contrasts with Eggleston's, offering a different yet equally curious perspective. They share the same spirit of curiosity.

Marci — As mentioned earlier, The Family of Man, a companion book to the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) 1955 exhibition in New York, is a book that I was exposed to over half a century ago and have on my shelf today. It explores universal themes of human life, no matter where in the world, including birth, death, growing up, falling in love, and more. It’s also one of the main aims of my work—to show that we are all more the same than we are different.

Satomi Sugiyama

Satomi was born and raised in Osaka, and having spent half of her life in Los Angeles, she tries to incorporate both her Japanese and American sides into her photography. She’s been shooting strictly on film for the past two decades, and her work ranges from portraits and fine art to experimental and street photography. Satomi was a guest curator for Anarchyº1.

Colin Czerwinski

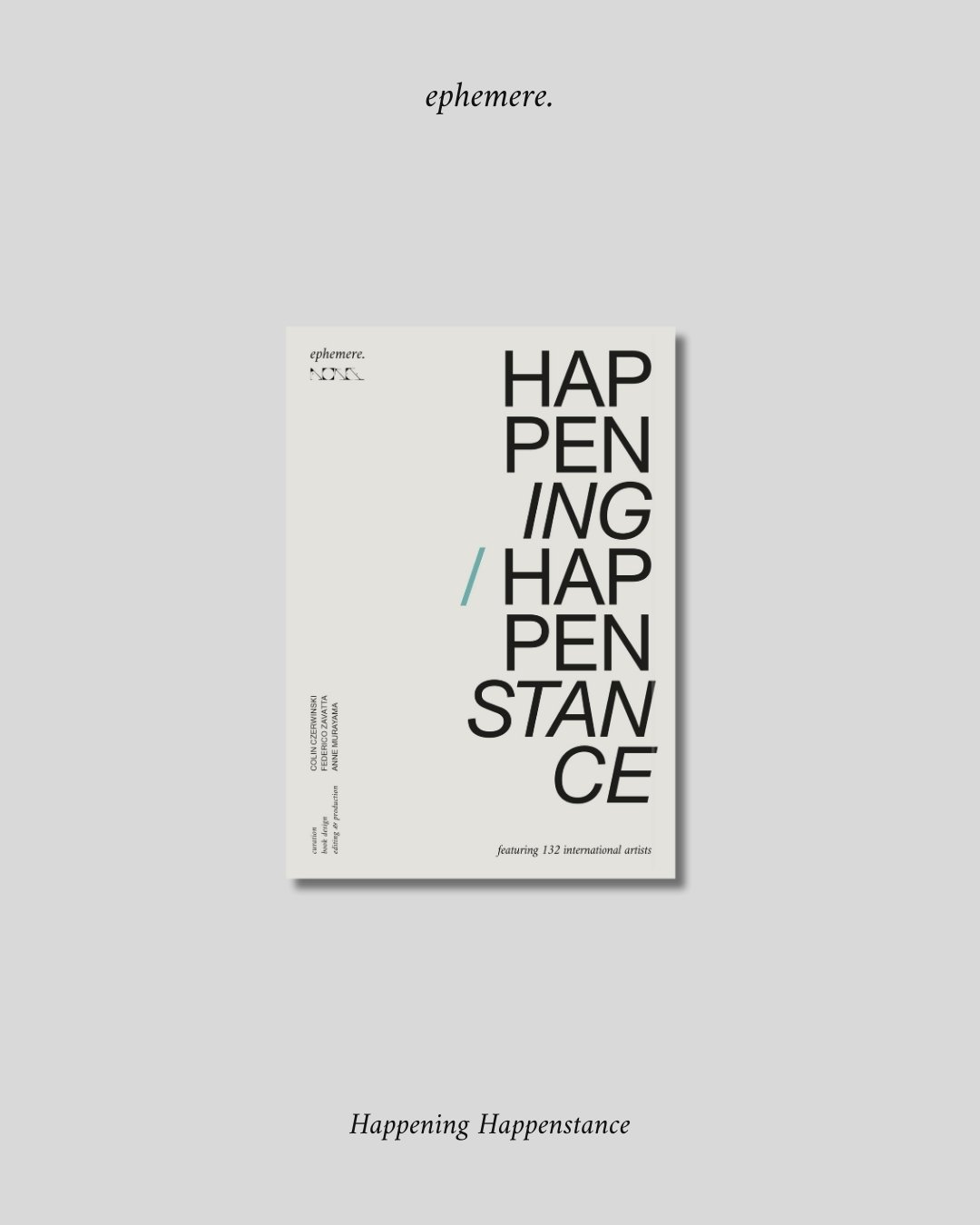

Colin is a photographer based in the United States. He’s the founder, curator, and editor of NOICE Magazine, a photography publication. Colin was a guest curator for Happening Happenstance.

Marci Lindsay

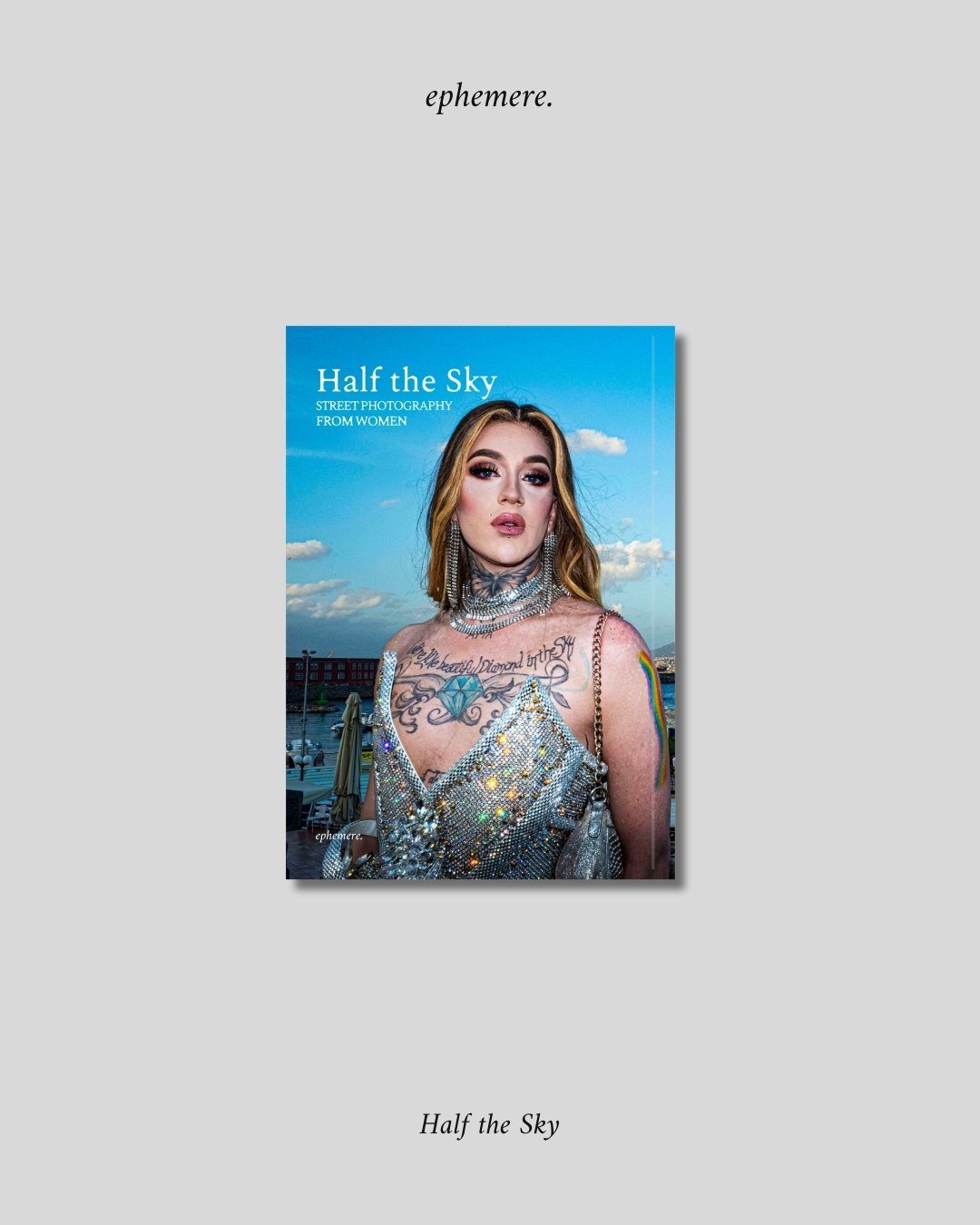

Marci is based in Washington, DC, and has been shooting street photography for about seven years. She’s a member of the DC Street Photography Collective and her work has been exhibited at home and abroad. She curates on multiple Instagram hubs, including Street Macadam and Women in Street. Marci was a guest curator for Half the Sky.

Anarchyº1 is a striking black and white photobook born from ephemere.'s inaugural open call and first group exhibition. This compendium of monochromatic images spans diverse genres, styles, and themes, presenting a picturesque chaos that epitomizes mono-mania. Featuring 143 photographers from around the globe, Anarchyº1 showcases a rich tapestry of perspectives. Guest curators Satomi Sugiyama, Trey Derbes, and Jim Herrington, each with a unique eye for black and white photography, collaborated with gallery founder Anne Murayama, who herself is devoted to the craft and aspires to make Anarchy an annual series.