Indonesia Photo Fair 2024

In a series of three interviews with various stakeholders—a Fair Director, a Publisher, and an Author—at the upcoming Indonesia Photo Fair in Jakarta (Sep. 5-8), Anil Purohit invites their insights, thoughts, opinions, and plans around photography: its role and function, acceptance among masses, marketability as artwork, the art, craft and future of photo books, their role in storytelling, and photo fairs, their function and logistics among others.

Exclusive Interviews

Cristian Rahadiansyah — Director at Indonesia Photo Fair

Vandy Rizaldi — Author of Sebelum Semua Pucat Pasi

Anne Murayama — Curator at ephemere.

ephemere. at Indonesia Photo Fair 2024 (Coming Soon)

Priming Photography for Art

Interview with Cristian Rahadiansyah

“ “Photography as artworks is yet to be valued as compared to visual artworks in the contemporary Indonesian context.””

Art occupies a peculiar place in the ‘value’ of things.

Unlike products that solve a functional problem and/or ease living in some tangible way, saving time, effort, and money, art does neither. Assuming most functional products have competition, allowing their price point to be compared with similar products to arrive at their quoted price worthiness, artwork has none. Neither does art conform to conventional models that arrive at product value via material and wage costs. Absent these, artwork relies, among other intangibles, on the perception of value based on social status derived from owing it and to an extent on emotions it evokes; artistic skill, effort, and uniqueness factor actively in the mix. And art as understood conventionally has a long and storied history to fall back on.

Now try and sell photography as art and the chips scatter quickly, randomly. And it’s easy to understand why photography as art is a hard sell to the masses, more so in the context of the art market. Its perception as effortless, easily reproducible, and lacking uniqueness strips it off the redeemable factors that ‘conventional’ art can count on. The exceptions however are not the rule.

Further muddying the pond are interminable debates between opposing camps over whether photography should be considered art, one that’s likely continued since photography’s early days, following the Daguerrian excursions.

It’s in this hot mix that Cristian Rahadiansyah, Director of Indonesia Photo Fair (IPF), chose to step into. IPF has positioned itself as an annual photography marketplace, a place to acquire photography works such as prints and photobooks.

““The mediator of the inexpressible is the work of art.””

In a freewheeling conversation on the eve of the IPF 2024 edition (Sep. 5-8), Cristian Rahadiansyah acknowledged that photography is yet to gain recognition as art [in Indonesia] compared to conventional visual art, and expressly stating that “IPF is an effort to increase that value – both monetarily and intrinsically – in the local market, and later in the regional market.”

He spoke of the challenges in widening and deepening the photography market in Indonesia, on reaching collectors, of helping photography practitioners rise to the demands of the marketplace, of the state of the market, of audience preferences, of what makes for impactful work, and plans for the future among others.

Photos courtesy of the IPF team

Anil Purohit: Indonesia Photo Fair (IPF) is now in its third edition and growing. Why did you feel the need for a Photo Fair in Indonesia, and what has IPF’s impact been on photography in Indonesia?

Cristian Rahadiansyah: Photography as a creative economy subsector in Indonesia is vastly growing. In 2020, the government reported that photography generated IDR5.9 trillion (approximately USD375,000) of the total national GDP. However, photography as artwork is yet to be valued as compared to visual artworks in the contemporary Indonesian context. IPF is an effort to increase that value - both monetarily and intrinsically - in the local market, and later in the regional market.

As of now, we are the only fair dedicated to photography in Indonesia. The fair has served as a platform for photographers to market their works. This has been especially important since the decline of mass media assignments for photographers.

Anil: How is photography as an art form and as a profession looked at in Indonesia, and what further developments do you want to see happen in the Indonesian photography scene?

Cristian: With photography being a popular mode of expression across generations - from X to Z - we have seen it being naturally appreciated as an art form. There are also more jobs as photographers with the growth of wedding, event, and art photography. In the future, I hope there are more media as a platform for photographers to showcase their works, especially long-term documentary projects. I am also hopeful that the new generation of photographers, with the right support from the ecosystem, could create impactful works that provide fresh perspectives on contemporary issues in Indonesia.

Anil: As an annual photography marketplace, IPF has focused on publishers alongside artists. This is usually not common at photography events where the emphasis tends to be on photo exhibitions. What was the thought behind making IPF a place to find and acquire photography works (prints and books) instead of merely showing photo exhibitions?

Cristian: We see photo books as a medium to present works, they should not be considered “lower” as compared to photo prints. We recognize the role of publishers within the photography ecosystem, which is to find talents and curate their works to be publicly showcased.

The first two editions of IPF were organized as part of the Jakarta International Photo Festival (JIPFest). While JIPFest focuses on widening the photography audience by offering public-centric exhibitions among others, the Fair aims to shape the local photography market. It hopes to introduce photography works to existing art collectors and potential collectors such as new homeowners, as well as provide insights for industry practitioners to market their works.

Anil: How would you categorize the Indonesian photography market, and what are the issues (if any) facing it?

Cristian: The market is still in its early stages, and it needs the photography ecosystem to collaborate on increasing the value of photography works and showcasing the works in attractive ways to invite potential buyers. Looking at photographers, we see the need to equip them with a wide range of skill sets, including public speaking and personal branding.

Anil: Which of these photography market categories in Indonesia do you want the IPF to help grow in the future?

Cristian: We’d like to showcase photography works for new collectors - homeowners and young professionals included. We also would like to introduce these works to existing visual art collectors.

We also hope to see new photo galleries in the country, alongside state-owned galleries like Galeri Foto Jurnalistik Antara. With that said, we hope that Indonesian photographers will be able to market their works at prestigious fairs such as Paris Photo and Photo London.

Anil: Over 50+ artists are being represented with their prints at the IPF 2024. By making artist prints available to purchase, has this helped convey to the Indonesian public that photography can be collected as art, and how has the audience responded to acquiring books and prints at the IPF?

Cristian: At IPF, we position photography works as artworks - we select the works, we work with renowned art handlers to design and install the exhibition, and we give the artists the privilege to put a price on their works. By creating this environment, we believe that we have conveyed that photography is collectible artwork.

In the first two editions, we have seen a great enthusiasm for photo publications, possibly because the market - especially in Jakarta - has been exposed to photo books and zines through independent bookstores and book fairs. With prints, we have been trying to invite as many potential collectors within our network as possible. Some of the artists have also been very active in promoting their works to potential buyers. We believe that kind of collective effort will soon shape the market.

Anil: Which photography subjects and themes generally interest visitors to IPF that they would consider acquiring for their homes and offices?

Cristian: In the context of photo prints, local art collectors prefer conceptual works, while homeowners tend to pick “beautiful photos” including travel and wildlife. In the case of books, they are easier to market because the audience has been exposed to book fairs and online bookstores. We have also seen Indonesian photographers produce good quality books with varied themes and experimental presentations, so the audience has more options to pick and choose.

Anil: ephemere. is exhibiting its publications for the first time at IPF 2024. What were your thoughts when deciding on including ephemere. as an exhibitor?

Cristian: The third edition of IPF marks the first time the Fair worked with overseas publishers. We hope to expose the audience to new and relevant book presentations to widen their references and ephemere. ticks those boxes.

Anil: Many Indonesian photographers have their work published in ephemere. books. What do you feel is driving the interest of Indonesian photographers, and what subjects and themes do you think they should pursue with their photography to be able to exhibit their prints and books at the Indonesia Photo Fair?

Cristian: The priority lies not within the subjects, but the concept and narrative that motivates a work. We believe that a strong concept and narrative could help create an impactful work. We can learn from visual art in this context, in terms of creating a strong concept and narrative.

Anil: What goes behind the scenes in preparing for and organizing the Indonesia Photo Fair?

Cristian: The biggest homework for the Fair is finding a venue. It is very tricky to find an event space in Jakarta with good quality and sensible pricing that is also accessible via public transport. We are very excited to return to Taman Ismail Marzuki, Indonesia’s first modern arts center, following its redesign - five years after the first edition of JIPFest was held there.

In this edition, we work with a lean yet effective team of 9 members to organize a print & book fair, a photo market, a series of fringe events, 10 talks, and 2 walking tours in 4 days.

Before Everything Turns Pale

Interview with Vandy Rizaldi

“Can you imagine a randomly placed bench or washing basket, surrounded by flowers and the vibrant colors of the dense houses, being replaced by a pale white fortress?” Vandy Rizaldi asks me without actually expecting an answer.

As the author of the photo zine “Before Everything Turns Pale”, it’s a question Vandy likely poses to himself, incredulous at the change that is erasing much of the once lively neighbourhood in Yogyakarta he revelled and delighted in exploring. Driving this change is a revitalisation project to restore the historical values of Yogyakarta’s philosophical axis area, among which is the old fort that traces its origin to the treaty of Giyanti in 1755 that divided the empire of Mataram into two, Surakarta and Yogyakarta.

The fortress surrounds the Yogyakarta Palace area and featured prominently in the subsequent power struggle between the Dutch, the British and the Sultan of Yogyakarta, witnessing furious attacks, desperate defense, unrelenting sieges and the flight of a queen during the Java War.

As can be seen elsewhere around the world, the drive to restore national prestige, be it modernisation of infrastructure, or development to serve a burgeoning population, or renovation of historical precincts, the transformation comes at a cost, often of settled communities relocated to make way for the ‘change’.

It’s toward this cost that Vandy Rizaldi turned his lens on.

In his photo zine, Sebelum Semua Pucat Pasi (Before Everything Turns Pale), winner of the Best Dummy Award at Jakarta International Photo Festival 2023, Vandy Rizaldi parses remnants of life in a series of occasionally surreal but invariably haunting images – of signs of life left behind, cold to the touch yet pulsing with life slowly petering out.

While the revitalisation of the historical area will centre a significant part of Yogyakarta’s history in the consciousness of Indonesia, particularly Java, as a living testimony to the past, the project, and the accompanying displacement, is drawing mixed emotions among those whose homes and livelihood have been impacted.

Vandy tells me of meeting a corn soup seller who felt proud of contributing to preserving history and the area’s heritage even though his house was earmarked for demolition.

Sebelum Semua Pucat Pasi strings together spaces anchored by objects that speak to life that once was. Where glimpsed through holes punched in walls the once safe spaces remind of a nurturing suddenly aborted. In dwelling on the scenes I could not help but wonder who these people were, and what they might’ve been if left to their own devices, and of how, as Vandy concludes later, “everything eventually comes to an end.”

In its essence, Vandy’s poignant portrayal of displacement and loss serves to record signs of life and livelihood before they themselves “turn pale”, disappearing altogether in short order. As if they never existed!

Glimpsing loss transforms grief into remembrance, and over time, recollection, before giving way to reflection.

It’s probably the best outcome a record of loss, of the living, can hope for!

Join me ringside as Vandy talks about his approach to visual documentation, of his motivations and experiences exploring the neighbourhood with his camera, the making of his photo zine, his interests and future plans.

Photos courtesy of Vandy Rizaldi

Anil Purohit: Congratulations on winning the Best Dummy Award for your book/zine “Sebelum Semua Pucat Pasi” at JIPFest 2023, and its subsequent publication. How does it feel to win the award and see your work published?

Vandy Rizaldi: Thank you so much! Winning the Best Dummy Award and seeing my work published is an incredible feeling, especially since this zine is my first experience with the photobook/zine medium. But honestly, this work would never have seen the light of day without the support of those around me, especially Prasetya Yudha from SOKONG! He’s not only been my editor but also the driving force behind the zine’s success. His brilliant contributions are what truly make it shine.

Anil: Tell us about your area of focus in choosing stories to photograph.

Vandy: I usually work with music and sound, which is what I’m known for. When choosing stories to photograph, I think of it like the difference between just hearing and truly listening. I aim to capture simple, everyday moments and reflect what I see, just as many other photographers do.

Anil: How do you go about preparing for your photo projects?

Vandy: Considering my background, I see myself more as a 'leisure' photographer. I’ve never had formal assignments, so I don’t face any pressure and use just a portable camera. This lack of pressure results in a laid-back approach: sometimes the context, stories, and narratives drive the snapshots I take, while at other times, the snapshots themselves reveal interesting details that I then explore further.

Anil: What made you take up this project to document the residential areas affected by Yogyakarta Special Region’s revitalisation project to restore the fort?

Vandy: I’m not the first photographer or artist to cover these stories, but it feels strange that the narratives behind the revitalization process have become quieter over time. Another reason is that this area is one of my favorite jogging tracks. Each time I visit, I see new and interesting details in the scenery and everyday lives of the people. Can you imagine a randomly placed bench or washing basket, surrounded by flowers and the vibrant colors of the dense houses, being replaced by a pale white fortress?

Anil: Since Yogyakarta is the only region headed by a Monarchy in Indonesia, how is it different from the rest of the country?

Vandy: The main difference is that the governor and deputy governor always come from the royal family. Some people forget that in a democracy, power should be with the people. But here, it feels more like sultan’s word is final and can't be questioned.

Anil: What were the challenges you faced in documenting the residential areas affected by the reconstruction of the fort that surrounds the Yogyakarta Palace area?

Vandy: The challenge is that I’m not from Yogyakarta, and some locals feel only residents should talk about local issues. Because of this, there’s a clear distance between me and the affected residents. Instead of trying to bridge this gap directly, I choose to embrace this boundary and reflect it in the zine.

Anil: Residents facing displacement from the loss of their home and livelihood face uncertain times. How do you plan your visuals to effectively convey their loss? What visual approach do you take?

Vandy: With the conditions I mentioned and the bittersweet smiles of the residents sharing their stories, I realized I couldn’t fully capture their dilemmas. So, I focused on photographing the scenery to let it speak for them. Colors, which symbolize diversity and vibrancy, still stand out even as their homes become ruins. My editor also enhanced the zine to create aspatial, immersive, and tactile experience.

Anil: Any experiences with the displaced people or when exploring the affected neighbourhood while photographing the project that you would want to share?

Vandy: One memorable experience was meeting a corn soup seller whose home was soon to be demolished. He had this bittersweet smile I mentioned earlier; on one hand, he felt proud to contribute to preserving history and the area’s heritage. On the other hand, he was deeply sad about losing the home he’d lived in since birth. He hoped that the relocation process would be handled with compassion and respect.

Anil: Since historical monuments are important to the sense of identity of the people, reconstructing them to recreate past glory is not only an important way to connect with the past but can also help generate commerce by way of tourism. So how do you as a photographer see the story where the need for reconstructing the past clashes with residential homes? How can the balance be achieved between both?

Vandy: From the stories I’ve seen, the people affected seem to have found their own way to balance things—a really deep acceptance. It’s one of the most human experiences I’ve ever felt. They remind me that, in the end, nothing is worth too much struggle or regret. The title 'Sebelum Semua Pucat Pasi' or 'Before Everything Turns Pale' reflects this too, reminding me how everything eventually comes to an end.

Anil: What changes on the ground do you hope and want your zine “Sebelum Semua Pucat Pasi” to achieve?

Vandy: Nothing really. I just see myself like those citizen journalists who use their phones to share what’s happening around them. It’s simple, nothing fancy—just capturing things as they are. That’s what I tried to do with my zine, but with a little bit of my own style, like how they edit their videos. Once again, I’m really lucky to work with my editor. Without them, this zine wouldn’t happen.

Anil: Tell us about your role and work as a member of Ruang MES 56, an artist collective based in Yogyakarta.

Vandy: When I first joined MES 56 years ago, I was put into the management and programming team. With my background in performing arts and music, I’ve always been a bit of an oddball there. But being the odd one out has its perks! Now, I’m the go-to person for anything audio-related, from giving sound advice to recommending the best wireless earphones. So if you need tips on speakers or just want to chat about music, I’m your guy!

Anil: What photo projects are you planning to work on in the future?

Vandy: Currently, I’m working on a laid-back project about public transport. I’m also waiting for my visa to be granted for a residency in Beppu, Japan, later this year, where I plan to focus on image-based projects. Fingers crossed!

The Photobook and ephemere.

Interview with Anne Murayama

““In the photobook, the sum, by definition, is greater than the parts, and the greater the parts, the greater the potential of the sum.””

We may never know by whom or when the Camera Obscura effect was first observed, nor whether it was by accident or by design, more likely the former. But one thing is certain, it would’ve evoked a sense of delight before giving way to wonder at the possibilities that projection of a scene onto a surface held, even if inverted and a tad out of focus.

That the inversion would be corrected by use of mirrors points to one thing – a continuing effort to record visuals, to show what one sees, to create a memory of a time and place, to communicate and share the visual experience with others – this is what I saw, experienced, and felt. Now I want to show you too.

It would take several centuries before fleeting projections of visuals via Camera Obscura could gain a level of temporary permanence with the use of light sensitive materials, and several decades more before the visuals could be “fixed” permanently as photographic images. Soon the desire and the need to share the photographic image with others would drive the reproduction/duplication of images.

To want to share experiences is a constant, to show what you see. Without it photography may never have materialized in its present form. And there would be no photobooks.

The photobook as a collectible object, a statement of purpose, a repository of memories, a keeper of an era, a story of a time, of a person, of a people, of places, a document of history, an expression of personality, a disseminator of taste, an harbinger of the future, an idiom of a generation, a catcher of cults, a repository of idiosyncrasies, a metaphor for a past, a chronicler of transformations – of cities, of countries, a bearer of traditions, of culture.

Just endless, the possibilities. If you can see it, you can show it.

This truly came home to me in a lecture Martin Parr delivered in a cosy room of an old building in Mumbai close to a decade ago, titled The History of the Photobook – A Personal Crusade.

Martin Parr’s was a personal crusade no less. A personal collection of over 12,000 photobooks would not qualify for anything other than a personal crusade to “ensure that the photobook, as both a version or revision of photography’s polyphonic histories and an aesthetic object in its own right, garners engagement within the context of world art history,” as Jnanapravaha, the host, put it, further adding, “it [photobook] empowers practitioners with a worldview of their discipline that is not mediated through the distant gaze of the art historian or curator.”

Photobooks take space. And it was time to create space for them in the art world as Cristian Rahadiansyah, Director, Indonesia Photo Fair (IPF), told me in an earlier interview, conveying the purpose of the IPF – to mediate a space for acceptance of the photobook, and prints, as works of art among the public.

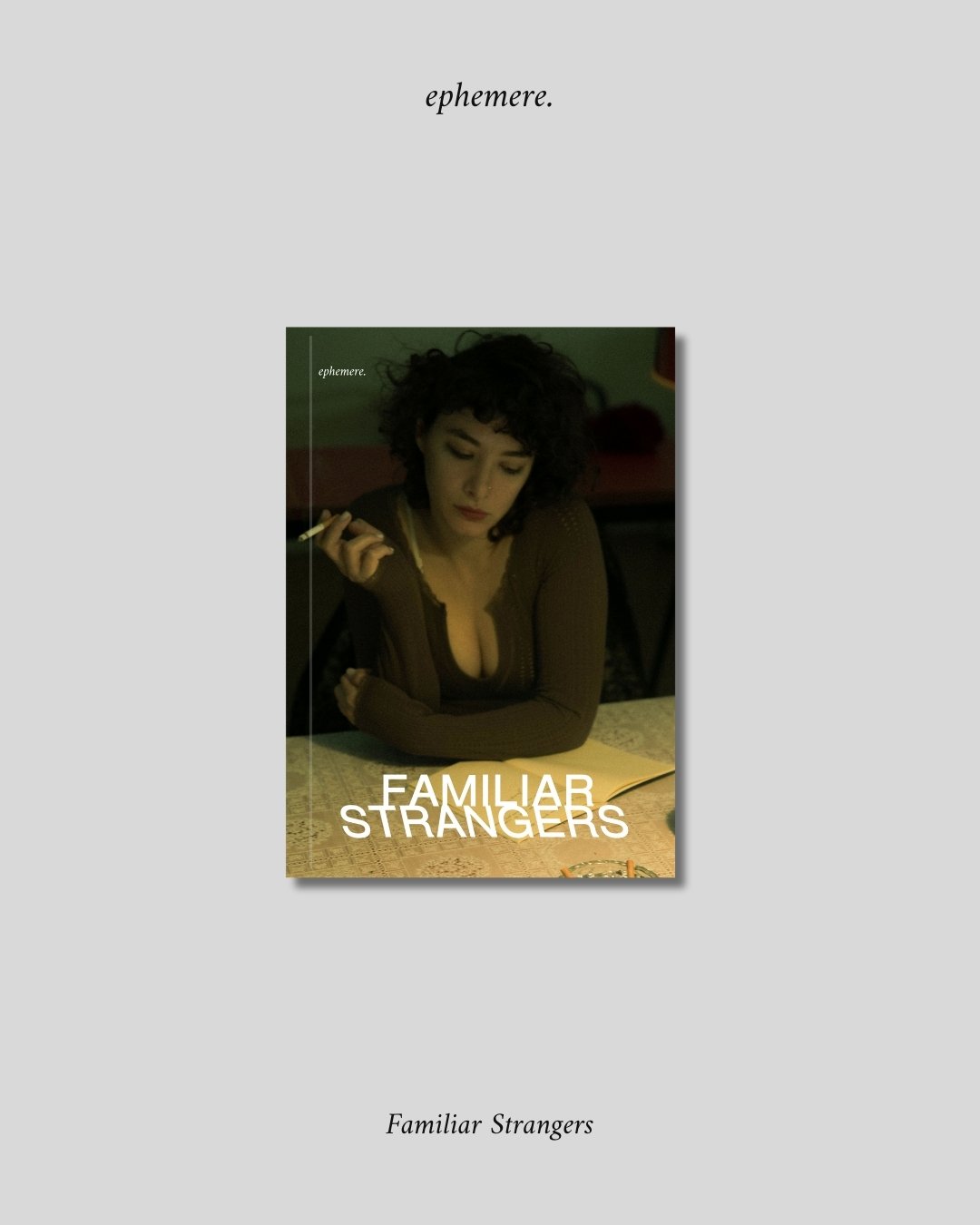

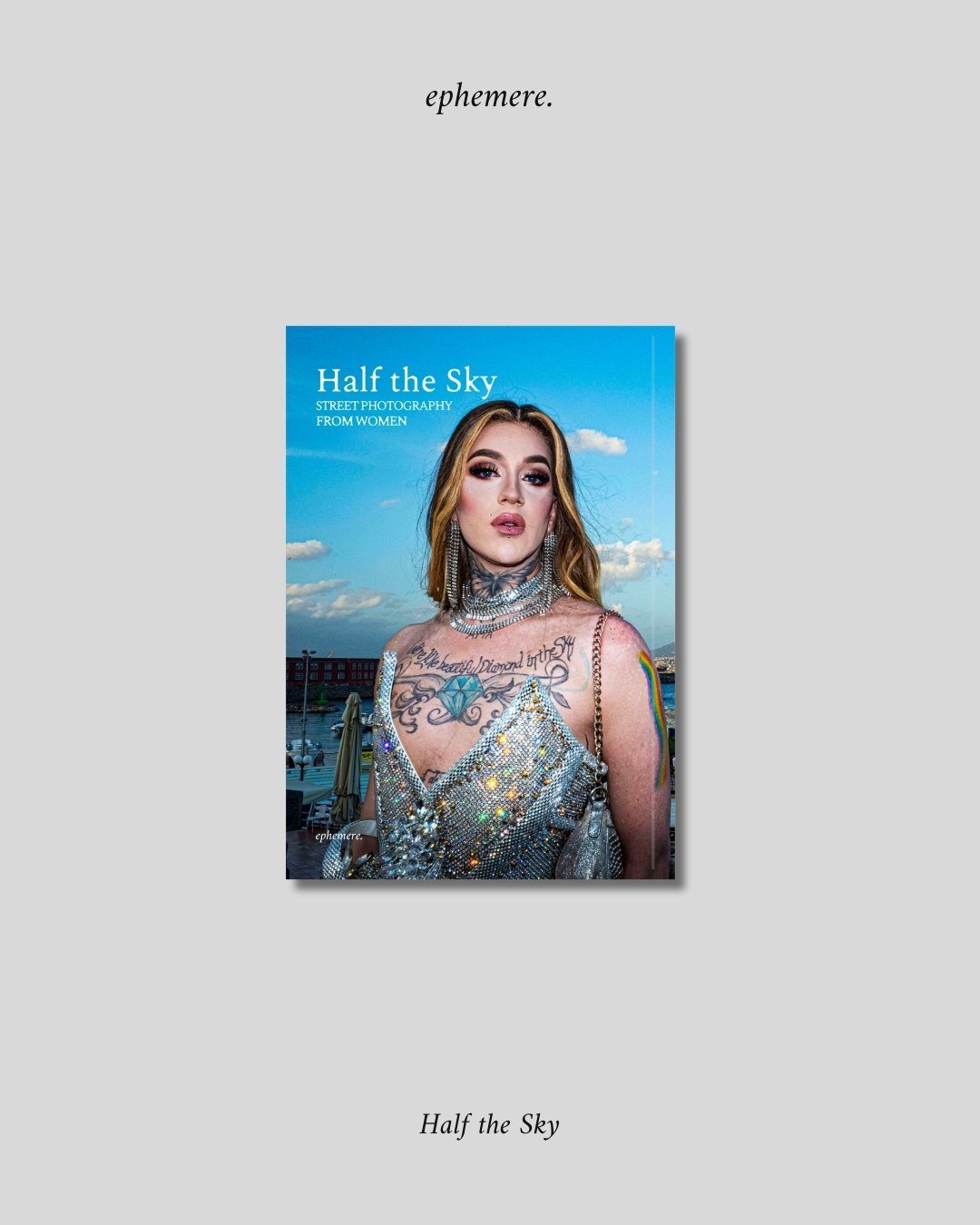

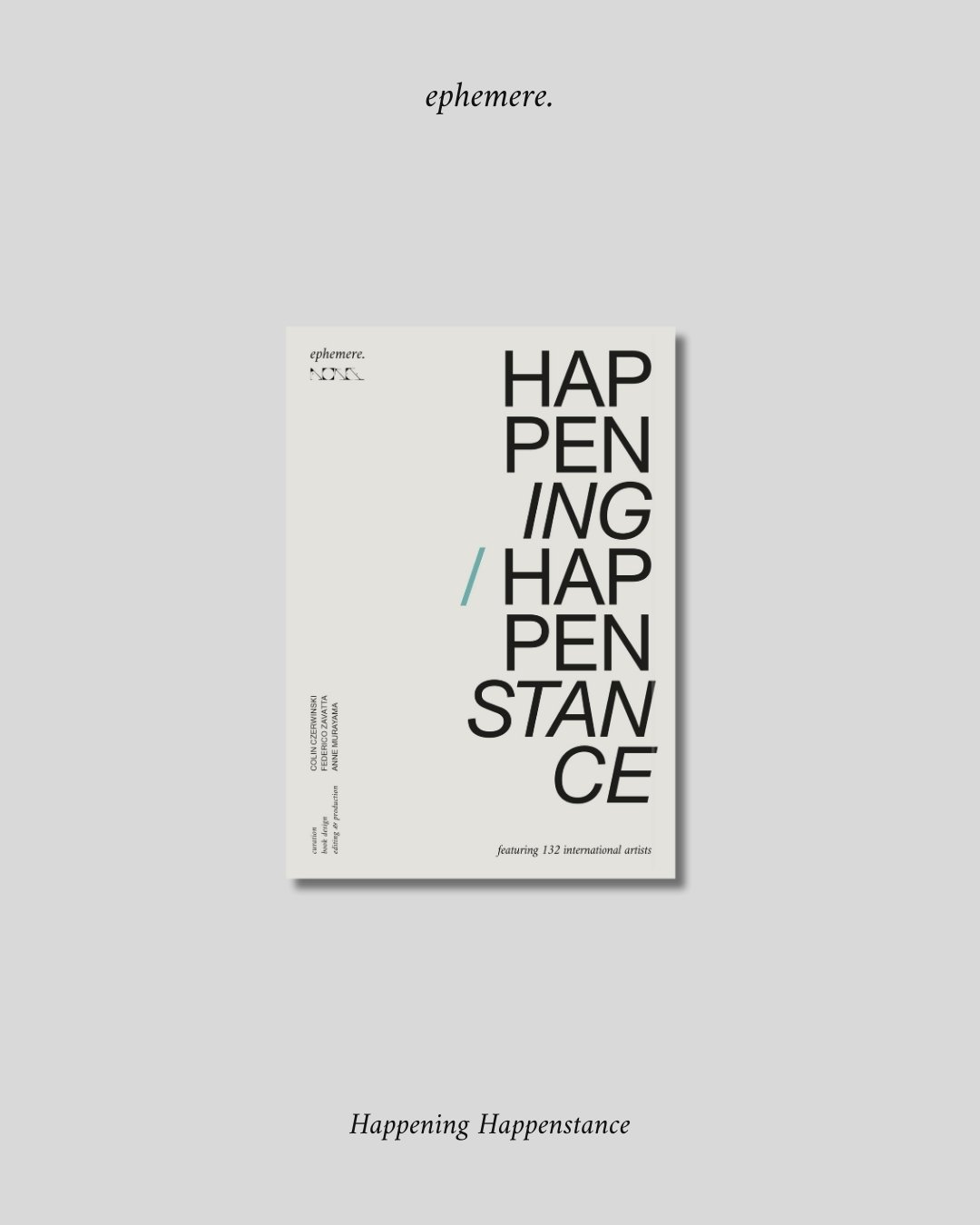

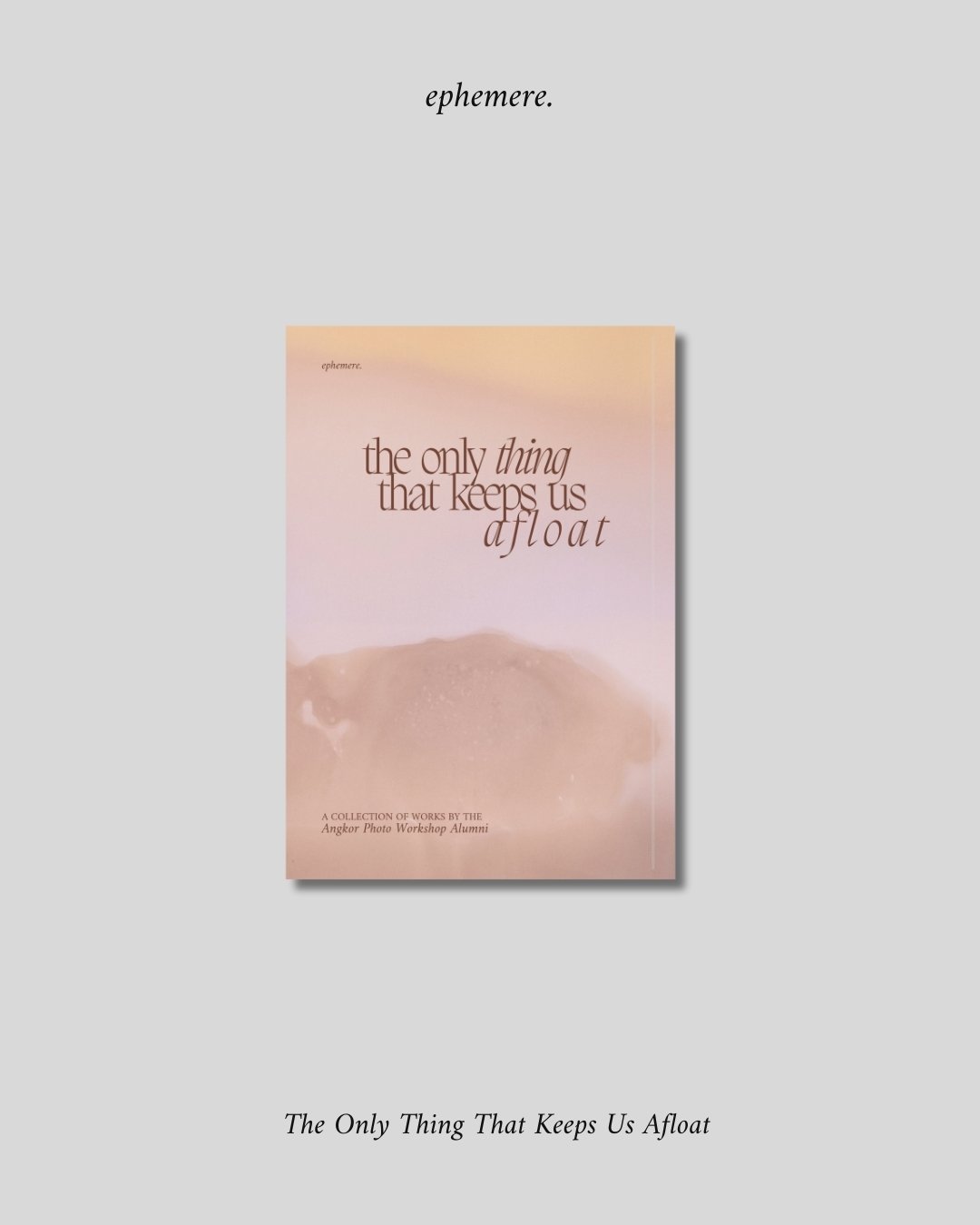

The push needs comrades in arms, and ephemere,. under Anne Murayama’s stewardship, is partnering with IPF to show its stable of eclectic photobooks at the photo fair this week in Indonesia.

““Photography finds its true purpose when it’s transformed into something tangible. Photobooks make photographs real, turning fleeting images into meaningful, lasting narratives.””

In the following interview with Anne I sought her take on photobooks and ephemere.’s journey in producing them, and partnering with IPF.

Anil Purohit: Where and how do you see photobooks fit into the photography world at large?

Anne Murayama: Photobooks have been integral to visual culture since Anna Atkins' pioneering work. They present and preserve photography, serve as a form of artistic expression, and are vital tools for education and inspiration. While social media has changed how we consume images, the essence of photobooks remains strong. With advancements in printing technologies, I believe photobooks can reclaim a central role in the photographic ecosystem.

Anil: Your thoughts on choosing to publish photobooks and why you see them as important to either starting or continuing conversations around photography? And ephemere.’s larger vision and mission around photography?

Anne: Photography doesn’t end with the click of a shutter. It finds its true purpose when it’s transformed into something tangible. Photobooks make photographs real, turning fleeting images into meaningful, lasting narratives. At ephemere., we aim to champion visual literacy, creating photobooks that spark conversations and deepen understanding in the photography community.

Anil: Your thoughts on partnering with IPF and in what way do you see the ephemere. publications on display add to the IPF programme?

Anne: Our partnership with IPF feels like destiny. Thanks to Rosa Panggabean, my colleague from the Angkor Photo Workshops, I was introduced to the organizers, who graciously welcomed ephemere. We’re thrilled to have five of our collective photobooks featured in IPF’s Photobook section, each featuring a number of Indonesian photographers. I’m excited for them to see their work in print and hopeful that this inspires other photographers to engage in our future projects.

Anil: Your message to photographers contemplating publishing photobooks as to (a) the kind of themes and stories you think need to be covered, and (b) visual approach to communicate those stories?

Anne: The more personal, the better. I’m deeply drawn to photostories that explore identity and life experiences, especially how photography can transform memories—both good and bad—into something concrete and tangible. These stories resonate powerfully when they come from a place of authenticity.

Anil: Plans for the future around ephemere. photobooks?

Anne: ephemere. is still in its early stages, so my focus is on consistency and publishing meaningful work. Our publications are a threefold exploration of photographic storytelling:

Thematic Ensembles—Curated titles that unify diverse topics under central themes, fostering collaboration and creative dialogue within the photography community.

Personal Narratives—Publications that delve into individual photographers' introspective journeys, exploring themes like emotional struggles, mental health, and personal trauma, offering a platform for intimate expression.

Everyday Life and Beyond—Books that capture the daily and societal aspects through candid, diaristic approaches, inspiring photographers to elevate their visual stories beyond social media.

Anarchyº1 is a striking black and white photobook born from ephemere.'s inaugural open call and first group exhibition. This compendium of monochromatic images spans diverse genres, styles, and themes, presenting a picturesque chaos that epitomizes mono-mania. Featuring 143 photographers from around the globe, Anarchyº1 showcases a rich tapestry of perspectives. Guest curators Satomi Sugiyama, Trey Derbes, and Jim Herrington, each with a unique eye for black and white photography, collaborated with gallery founder Anne Murayama, who herself is devoted to the craft and aspires to make Anarchy an annual series.