Visual Zen: The Photography of Glen Snyder

In Glen Snyder’s photography, time is both a subject and a process. His series Yorumo Hirumo invites viewers to contemplate time’s quiet passage, where movement and stillness coexist in a delicate balance. For Glen, photography isn’t about freezing time but engaging with it, allowing it to unfold naturally. The choice of black and white, the use of motion blur, and his return to familiar places like the Tama River reflect his Zen approach: a mindful, repetitive exploration of the present moment. His work doesn’t trap time; it lets it resonate, asking viewers to embrace the transience of life and find meaning in what is, rather than what’s lost.

Mystery is a concept that has captivated me for years—a fleeting insight into destiny or a moment when disparate stories and intentions begin to intertwine. For as long as I can remember, it has been a profound force in my various attempts in life. It's also how I came to know Glen Snyder, a photographer, scientist, and Zen priest.

If you find yourself wondering how one can enter the spiritual realm, capture life through a camera, and also be a scientist, it's worth considering how such diverse roles can exist within a single person. Perhaps the answer is more straightforward than we think. In an age where new trends are often overexposed, we might not need to view this as yet another sensational story. Instead, we could explore the questions of how and why someone would choose to acquire knowledge and skills in these varied fields. The conclusions we draw often carry more weight than the fleeting first impressions that can leave us feeling overwhelmed rather than reflective.

© Glen Snyder

Glen's recent work, Yorumo Hirumo, left me with curious impressions. One of the first things a viewer can notice is a skillful interplay of time and movement in his images. The photographs of the Tama River transport the viewer to a place that has undergone significant transformation yet also depicts the tradition. Through contrast and color, Glen creates a harmonious dialogue between the past and present, allowing us to appreciate the remnants of old Japan. In this exploration, the camera in his hand becomes not just a tool for capturing images but an instrument for documenting life. It possesses magical qualities to it. If you spend enough time getting to know it, you'll uncover this enchantment and locate the mysteries beyond, just like Glen Snyder. On this note, the interview:

Guzal Koshbahteeva: Photography often captures fleeting moments, making it a fascinating interplay with time. In your opinion, what role does time play in your work, both in terms of the moments you choose to capture and the way viewers perceive those moments?

Glen Snyder: I don’t think too much about time when I am taking photos. I may notice those decisive moments where I just missed a photo. But since I take most of my photos near where I live, if the moment is not quite right, I know I can always come back a day later, a week later, or a month later to try again. I hope that my photography expresses some kind of timelessness that the viewer can relate to.

Guzal: I often find that movement in photography often seeks to capture a slice of dynamic time. How do you conceptualize the relationship between the static nature of a photograph and the dynamic qualities of movement within it?

Glen: I like watching old noir movies in black and white for inspiration. Of course, the cinematographer has the ability to direct the viewer's eyes from one place to another. In photography, we have the challenge of creating motion with static images. This might be through motion blur, either of the subject or the background. But there are other techniques as well. One is to have strong leading lines in the photograph to direct the viewer’s eye from one edge of the photo to another.

Guzal: How does your composition change when photographing movement in black and white compared to color?

Glen: Colors in motion blur can distract from the composition, so I guess that is one reason why I prefer black and white.

© Glen Snyder

Guzal: On a philosophical note, there seems to be a growing trend among photographers to return to film rather than relying solely on digital methods. Do you think this resurgence is driven by a sense of nostalgia for the past, and if so, how do you believe this longing for the era influences contemporary photography and its creative possibilities?

Glen: Since I have always used a film camera, I don’t think it’s a bygone era! But I use whatever is most practical. I prefer old lenses to modern digital cameras because I don’t like how focus-by-wire lenses handle. Recently, I have been doing medium-format film photography with a Pentax 67. There are limitations that film has, but the resolution of a 6x7 film negative is greater than that of modern digital cameras. Even with 35mm film, which tends to be more grainy, the character of the grain seems to me to be different from that of film emulations done in camera or in post. In any case, I recommend that everyone give film photography a try now and then. I feel that the limitations of a single film ISO and a limited range of shutter speeds imposed by film cameras can improve one’s photography skills can carry over to when one is taking digital photos.

Guzal: Sometimes, I feel that a single photograph can have a melody to it, as if it resonates with a certain rhythm or harmony. Do you sense a similar 'melodic' quality in your photographs, and if so, how do you think this musicality influences the viewer's experience?

Glen: I’ve heard that some people listen to music when they take photographs. I just take photographs. I agree that there is some visual harmony in good photography, although it is somewhat improvised. In other words, “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing”!

Guzal: I appreciate your scientific background. Do you believe that this background brings a unique perspective or approach to your photography? If so, how does it influence your work, particularly in areas like technical precision or conceptual depth?

Glen: I like to think that photography is very much the result of a collaborative effect. In other words, my photography is not entirely my photography but is also an expression of the engineers who designed my camera, the chemists who created film and processing (and modern sensors as well), and all of the events (both natural and in human landscapes) going on around me. The idea that some people are exclusively mathematical or scientific while others are exclusively artistic or oriented towards the humanities starts to fall apart when we look at the collaborative efforts that bring about great photography.

Guzal: Are there specific elements or themes in your photography that you tend to avoid or dislike? What are they, and how do you navigate around them in your work?

Glen: I often take photos that include people without asking permission. Sometimes, I come across those in the photographs or people who know them, and I hope that if that is the case, they will be delighted with what they see. I remember after many trips to Iwate, a photographer friend shared a couple of years of photographs of me that he had taken. I was so happy to see them. So, while I want to have the freedom to take photographs that include people in a style that I like, I am not a fan of photography, where people are portrayed in a way that the person would perhaps be ashamed of where others see the photographs. So, alcoholics, sex workers, people passed out on the street or experiencing some kind of psychological crisis….not something I will photograph. I realize that some street photographers consider themselves documentarians and feel that if they were not to photograph these subjects then the historical record of present reality would be somehow whitewashed. But treating those who are in a bad situation as photographic objects is also not treating them in a humane empathetic way.

Guzal: As an artist navigating different cultural landscapes, how do you perceive the role of cultural identity in shaping your photographic vision? Do you think cultural influences are more of a guiding force or a constraint in your creative process?

Glen: I have now lived in Japan, and Costa Rica for longer than I have lived anywhere in the U.S. So, the U.S. is as foreign a place to me as anywhere else. While my Spanish is quite good, I feel that learning Japanese has been one of my great failures. Since I am practically illiterate here and work with an operating Japanese vocabulary of a child, it has forced me to focus my expression in photography. I hope that Japanese people will feel moved in some way by my photography, even if I cannot discuss it with them. The theme and intention of the photograph must be clear enough so that it resonates. As it is, if the photographs resonate with everyday life here in Japan, they often resonate with people from different parts of the world as well.

Guzal: I find your images, particularly those of people walking near the Tama River, to be incredibly touching and imbued with a poetic quality. Do you enjoy reading poetry, and if so, do you think it influences your work in any way?

Glen: I was trained as a Zen priest, and Buddhism has, for over 2000 years, been imbued with verse. This was purely a practical matter in early Buddhism since there was no written record for several hundred years, so teachings were handed down in verse that could be more easily memorized. In the U.S., Zen is much newer and was influenced heavily by the Beat Generation. Allen Ginsburg was a close friend of Robert Frank, as I understand it, and was an outstanding photographer in his own right. So I would like to think that my photography cannot be separated from the Beats or from Buddhist poets, hermits, and wanderers such as Ryokan in Niigata, or Matsuo Basho who journeyed to the interior of Tohoku, or Han Shan from Tiantai Mountain in China. In many cases, the element of the Journey is important in these poetic accounts. And I may be the opposite of someone who journeys about, as I generally stay in the same place and photograph those in the midst of a journey….either by train or walking along the Tama River.

Glen in robes

Finally, in addition to the contemplative imagery in the book, one of the most intriguing aspects for me is the meaning of time. Glen highlighted his emphasis on timelessness in the interview, which echoes the Zen philosophy that weaves throughout the work. By capturing moments in his images, I conclude that he invites viewers to embrace time rather than distance themselves from it, nurturing a sense of unity with the present. Like a Zen priest, Glen suggests that instead of viewing time as a separate force, we should immerse ourselves in it, becoming one with the moments he depicts.

It is rather curious that photographers, consciously or not, strive to chase time, attempting to trap it—if only for a millisecond—within their cameras' shutter. This pursuit raises a couple of compelling questions: what is it about these captured moments that resonate with us? or are we searching for a way to make sense of our ever-changing lives through these photographs?

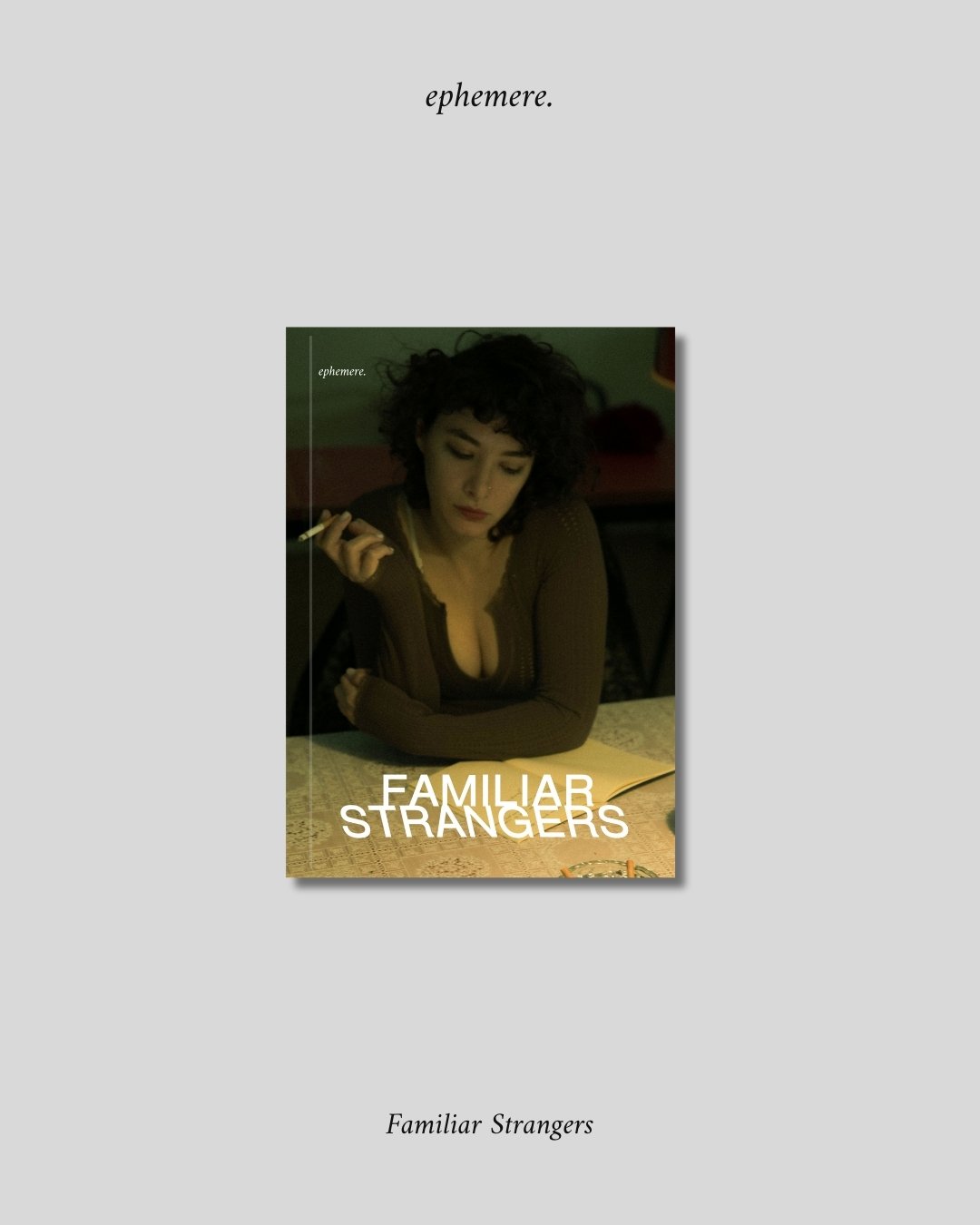

Drawing from Glen Snyder’s daily work commute, Yorumo Hirumo offers a unique view of life along the Tama River, which separates Kanagawa from the urban metropolis of Tokyo. This photo book coincides with Snyder’s first gallery showing at ephemere., featuring 92 pages of black-and-white photography that masterfully blends digital and traditional film techniques. The captions, influenced by a traditional Zen verse, delve into the relationship between light and dark, adding depth to the visual narrative. Hiro Arcode's Japanese translation further enriches the experience, making Yorumo Hirumo a cross-cultural journey through time and light.